There’s a point towards the end of Ghost in the Shell where Major Motoko Kusanagi is in serious trouble. A Section 9 operation has gone horribly wrong and now she’s all over the TV news, caught on camera in the act of executing a young man in cold blood. Kusanagi is remarkably calm about this and while waiting to testify, she asks her boss Aramaki for a look at the draft of his defense. His response is:

“There is no defense.”

Kusanagi looks at him, surprised, angry. And he pushes.

“Is there?”

That question, and the complex ethical grey area that it illuminates, is the space that Ghost in the Shell inhabits. Right and wrong, honesty and deceit, human and machine. Every line is blurred. Every line is crossed.

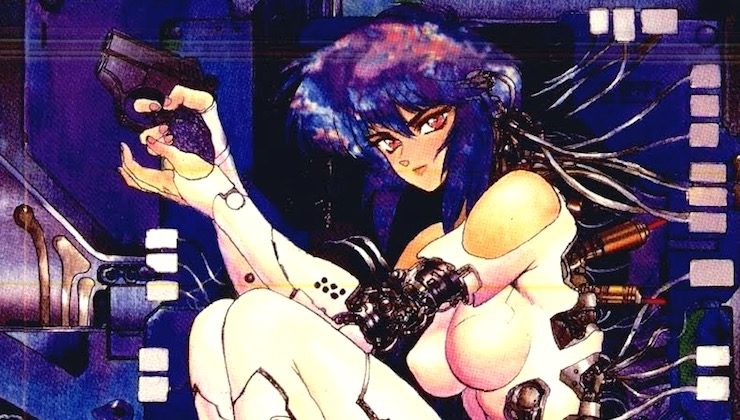

Written, drawn, and created by Masamune Shirow, Ghost In The Shell is nominally a police series. Major Motoko Kusanagi and her colleagues are part of Section 9, a counter-terrorism unit whose work is as murky as it is vital. Her second in command, Batou, is a cheerfully musclebound cyborg moving ever closer to a nervous breakdown of sorts. Other team members include perennial new guy Togusa and the aforementioned Aramaki himself. A small, precise older man who always thinks ten steps ahead, Aramaki is a boss who is as demanding and ruthless as he is loyal. The team is rounded out by their detachment of Fuchikoma, spider-like tanks equipped with a simple artificial intelligence who are far more individualistic than they first seem.

On the surface this is absolutely standard science fiction/police procedural fare, but within a few pages, Shirow turns that familiarity on its head. The first case we see Section 9 handle involves a factory where children are worked to death making water filters. One officer expresses horror at this and Kusanagi responds that the water filters are more important than human rights and people are cruel: humanity viewed as commodity. Humanity as the cheapest, most replaceable part.

That idea is built upon in a later story where the personal narrative of a minor character is hacked. The character’s entire justification for their actions is revealed to be a construct placed in their brain by a criminal. They have context, history, emotional reactions. All of them lies.

What makes this story so effective is not the horrific thought of having your life turned into someone else’s story but the fact that it’s played off as a joke. This is a world where identity is something that you rent, or own just long enough for someone else to realize its value. Nothing, and no one, is safe and it’s been that way for so long that everyone’s used to it. That’s a chilling idea, made all the more so by how pragmatically and unsentimentally it’s presented.

It also reflects the dark reality at the very heart of the book. One chilling scene suggests that robots who are becoming outdated are starting to attack humans. The same story sees a particular model of android, used as a communications medium, reprogrammed to attack their owners and cause horrific damage because that’s the only way a corporate employee could get anyone’s attention. Elsewhere in the book, a hobo camps undisturbed in the middle of a huge, automated building. Humanity is presented not even as a component this time, but as irrelevancy.

But it’s the final act of the book where things really take off: Section 9 encounter a puppeteer, someone capable of jumping between bodies. To complicate matters even further, the puppeteer isn’t a human but a spontaneously generated informational life form, something or someone truly new.

What starts out as a relatively simple intelligence operation becomes a story that, again, shines a light into the vast, troubling grey areas that these characters inhabit. The puppeteer is tricked into a specially designed “trap” body by Section 6, another Intelligence and Surveillance unit. S6 don’t tell anyone else what’s going on, and what starts out as a law enforcement operation quickly devolves in the face of political expediency, professional embarrassment, and fear—all of which clash head on with the needs of an unprecedented lifeform.

This is where Shirow really brings the moral uncertainty of the series to the fore. Not only do humanity and digital life collide, but Major Kusanagi herself is forced to confront the realities of her job and life. After an entire book in which scantily clad female bodies are used as communication systems, weapons, or what amounts to a complicated and ultimately useless pair of handcuffs, the Major finds herself facing a chance to be much more than she, or anyone else, could imagine. A chance for uniqueness, and freedom. The fact that this comes at the cost of potentially losing her entire identity is both a price she’s willing to pay and one she has little choice but to accept. Especially, as Aramaki points out, because there’s no defense for the status quo.

Ghost In The Shell isn’t just a cyberpunk classic, it may be the last cyberpunk classic. The Major’s journey, her evolution into someone more than human, mirrors the book’s own journey from the cheerfully nasty “Cyborg Cops!” narrative of early chapters into something far more complex and nuanced. Both Kusanagi, and her story end up growing into something greater than the sum of their parts and that, in turn, gives Ghost In The Shell the last thing you’d expect from a cyberpunk story, and the key to what makes it so memorable: hope for the future.

Alasdair Stuart is a freelancer writer, RPG writer and podcaster. He owns Escape Artists, who publish the short fiction podcasts Escape Pod, Pseudopod, Podcastle, Cast of Wonders, and the magazine Mothership Zeta. He blogs enthusiastically about pop culture, cooking and exercise at Alasdairstuart.com, and tweets @AlasdairStuart.

I love the attention to detail in GitS and Shirow’s other works (especially Appleseed). The plotting and motivations are complex but believable. Even the action scenes are a complicated dance that give you a sense of location and scale. And of course there is the gorgeous artwork.

The movie understandably focuses on the puppeteer story, but the preceding police procedural work gives a lot of characterization and context that I was sad to see stripped out.

Are we going to get a review of the new film at some point?

Bravo. I loved your analysis. It’s a great dissection of a story that will be remembered as a classic in hundreds of years.